More Fun & Brain Games with the 026 Trichord!

Much of the material covered here is derived from concepts which I first encountered several years ago in “Twelve-Tone Improvisation: A Method for Using Tone Rows in Jazz” (Advance Music) by saxophonist John O'Gallagher, as well as from guitarist Bruce Arnold (Muse-Eek.com), who has been performing, composing and teaching these concepts for a long time, and who recently turned me on to the joys of the 026 trichord and has helped me make sense of it all.

One source of those “026 joys” is the presence of a tritone (aka: augmented 4th, diminished 5th, #4, b5). Whether in the trichord's 2+4 (C-D-F#) or 4+2 (C-E-F#) formation, the tritone is always there – meaning there's a dominant function lurking - as in traditional harmony - with the urge to resolve somehow.

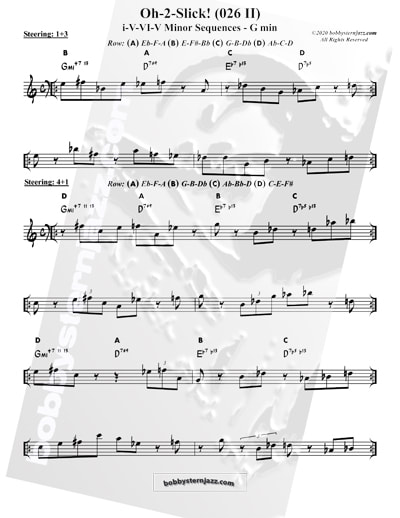

Since the release of the previous volume “Oh-Two-Six”, I've managed to obtain some additional clarity as to how 12-tone rows (comprised of the 12 non-repeating tones of the chromatic scale) are constructed. Thanks again to Mr. J. O'G's aforementioned book, which introduced me to the concept of “steering” as it pertains in particular to 026.

“Steering”, originally conceptualized by Dutch composer Peter Schat (1935-2003), describes the interval distance between trichords (or tones) in a particular row, and is a critical element in how that row is constructed.

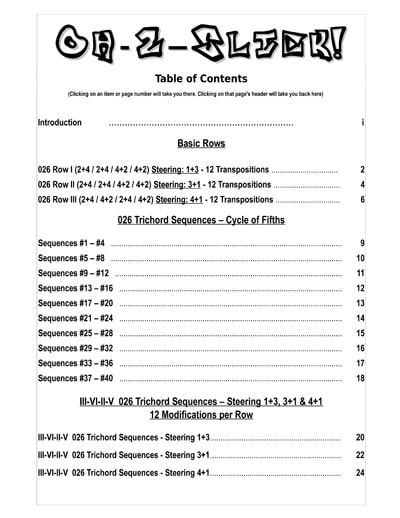

Below are the 3 possible row constructions (“steerings”) for 026 (2+4), shown in all 12 pitch levels:

Row I: Steering 1 + 3

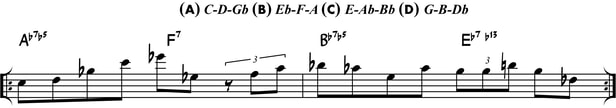

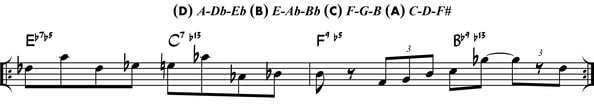

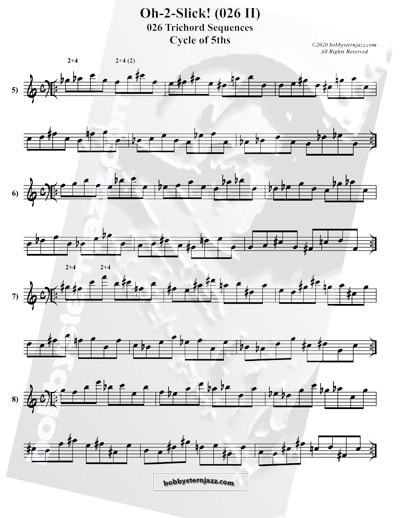

Perpetual motion cycle sequences involving 026 trichords (2+4 & 4+2) descending by perfect 4ths or semitones, serve as warm-ups for the I – VI – II – V, as well the minor i – V – bVI – V sequences that follow. These cycle sequences do not necessarily take the row into account, but are designed to facilitate 026 movement around the cycle. These 3, 4 or 5-note units can usually be heard as dominant 7th chords (and their tritone substitutions), but can represent any chord formed by the alternating Whole Tone Scales.

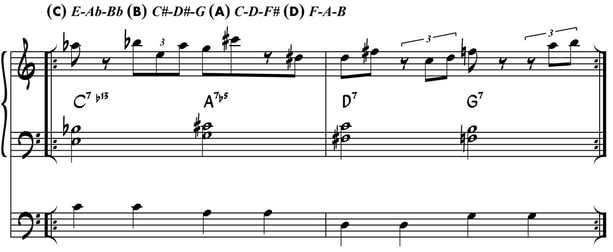

Ex. 1 - 026 4 + 2 & 4 + 2 – Perpetual Cycle Sequence

Ex. 2 - I-VI-II-V - Steering 1+3, Set (C+B+A+D)

The letter designations above the staff indicate the order of the trichords within the row, called the “set”. In the above example, the original row is (A) C-D-F# (B) C#-D#-G (C) E-Ab-Bb (D) F-A-B (Row I – Steering 1 + 3, as mentioned).

By juxtaposing the order of the trichords to (C) E-Ab-Bb (B) C#-D#-G (A) C-D-F# (D) F-A-B, in order to sound “good” with each 7th chord (a matter of individual taste), the above melodic line - designated as Set C+B+A+D - was created.

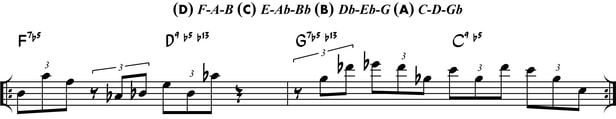

In the next example, the same Row & Steering 1+3 (meaning the same exact 4 trichords), are employed over a I-VI-II-V starting with F7. The result: Set D+C+B+A.

Ex. 3 - I-VI-II-V - Steering 1+3, Set (D+C+B+A)

This goes for steering 3+1 and 4+1, as well.

Study the folowing examples. Notes within a trichord can be repeated, but not elsewhere in the row.

Ex. 4 - I-VI-II-V - Steering 3+1, Set (C+D+A+B)

In this chapter, there are 4 examples for each of the three Rows, transposed to each of the 12 pitch levels (keys).

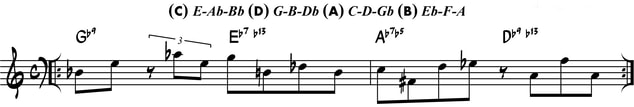

The graphic below depicts a i-V-bVI-V chord sequence in A minor. Steering 3+1 with set D+B+C+A describes the melodic line.

Ex. 8 - i-V-bVI-V Steering 3+1, Set (D+B+C+A)

Ex. 9 - i-V-bVI-V Steering 4+1, Set (D+A+B+C)

It's been said that John Coltrane was first exposed to the concept of trichords in the late 1940's in Philadelphia through his studies with guitarist Dennis Sandole. It began to manifest in his final work almost twenty years later.

Because of the presence of the tritone, the 026 trichord – and subsequently, its rows and sequences – is probably the most familiar sounding (by close relationship to the Cycle of 5ths) and therefore, the easiest to hear and work with in a traditional sense.

B. Stern

RSS Feed

RSS Feed