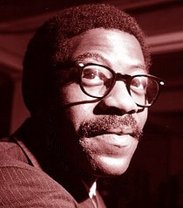

Yellin on Henderson:

A candid interview with saxophonist Pete Yellin

Pete 'n' Joe

Pete 'n' Joe Sundar, then a doctoral candidate at NYU, interviewed Pete as part of his 540 page dissertation, bearing the title "An Analysis of the Jazz Improvisation and Composition in Selected Works From the Blue Note Records Period of Tenor Saxophonist Joe Henderson from 1963-1966", leaving no doubt as to who, what and when, and which he was most generous to have shared with me recently.

The main subject and focus of the interview is, of course, none other than tenor saxophone titan Joe Henderson, with whom Yellin had a long friendship and musical relationship, dating back to the early 1960's.

Pete Yellin passed away on April 13, 2016 at age 74.

Interview © 2001 by Sundar Viswanathan. Used here by permission.

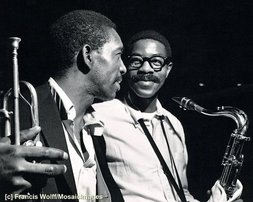

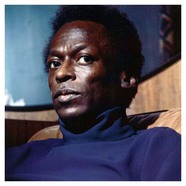

KD & JoHen

KD & JoHen PY: Well, of course, everybody knew Joe from his great playing and Joe was in Brooklyn... he started a Big Band, and just from word of mouth friends of mine told me he was changing personnel around a lot... people were coming and going, you know, 'cause a lot of people were not available to make rehearsals and so forth.

And so one guy told me 'Why don't you call him... and tell him you're an alto player and you want to play in the band." So I did. He said 'Come to the rehearsal'. So I came to the rehearsal, and I met him. At the rehearsal....he never heard me or anything.... we sat down and played and he was fine with it, and he said, “Come to the next rehearsal” and so on. I got to know him, 'cause he was very affable and very friendly, and he also lived right near me. He was living in Brooklyn and so was I. I had a car and would drive him home sometimes after rehearsals.

SV: What area were you guys living in? What area of Brooklyn?.

PY: He lived in Brooklyn Heights on Montague St. and I lived on Eastern Parkway. But I would drive him home. I just loved hanging out with him. And so, I would go to his pad and hang out with him and then drive him home from rehearsal and then we'd just hang out all night, you know, unless he had something to do, but nine times out of ten he didn't. So we'd just sit and talk and talk, like six hours at a time in his little pad up there. We had other interests in common. He was studying Eastern Philosophy, y'know. That's when he was into Shade of Jade, and Punjab, and those tunes that he wrote.

He was into all that, eclectic and Eastern Philosophy, and he was reading the Bhagavad Gita, I think it was? And he was reading Thomas Mann, you know, all the things that the '60's people were into — about drugs, about acid, about this, about pot, y'know. We were all into that. Everybody was into it. So we had a lot in common. We would sit and talk hours and hours about stuff - politics, race, music and influences and everything and anything. He knew that I had some Classical background at Julliard, so he was interested in getting into that and learning to play some of the classical pieces, but he already had some classical training himself, in Detroit.

SV: From Wayne State?

PY: Yeah, from Wayne State - he studied with Lawrence Teal, who's a famous saxophone teacher in Michigan.

SV: Right. Did he study saxophone or did he study clarinet?

PY: Yeah, saxophone... and as far as I know he didn't study anything else but he did pick up flute, actually, 'cause Herbie (Hancock) wanted him to play some flute, some bass flute or alto flute or something on one of the records. So, in order to play Herbie's book he had to do that.

SV: So, in that, going back to the Big Band project, was that the one co-headed by Kenny Dorham?

PY: Yeah, originally. But when I got to it, Kenny was supposed to show up and never did. Kenny was a little bit spacey and hard to pin down and maybe he wasn't really into it, so Joe kinda broke it off with Kenny and just took it over himself.

SV: What tunes were you doing at the time, do you remember which..?

PY: Mostly Joe's originals - “Shade of Jade”, he used to come in with “Isotope”,... he used to come in with 12 bars at a time and he would pass the music out. The band was an all-star band. All these incredible cats - like I said, Chick (Corea) played in the band and, Ronnie Mathews, and Roy Haynes played in the band and Joe Chambers.. y'know, different guys all the time.. Garnett Brown and Slide Hampton. Trumpet section was all all-stars all the time..who'd show up was like Jimmy Owens, and Randy Brecker. Lee Konitz played alto sometimes, it was just unbelievable.

SV: So Joe didn't have, like, the full pieces of the charts in? He sort of put it together?

PY: Yeah, he was listening a lot to everybody, Ellington and Dizzy Gillespie Band - you could hear it in the writing - and he would just come in with the 8 bars. He would just take one of his tunes, Serenity, or Punjab, The Kicker, or a blues., all the things that he recorded with Blue Note or that he recorded with Horace – or anything that he would write - he would come in with a chart on it. And it would just be, like, the melody - and that would be it. Then he would voice - have an interesting approach to the melody - Without a Song or whatever he wrote in and change the harmony. We'd try the first 32 bars, and he'd play a few choruses.

There was a guy taping it at rehearsals. The guy who ran the studio had a setup to record. So he'd record Joe. I mean, people love Joe. So they'd do favors for him. He was such a sweet guy and a great musician, he just had such a sweet way about him, and the band was so good that people would just do him favors, man. He had the tape with the melody with the way he voiced it. He'd solo and then he'd let one of us solo, whatever, and then he'd play the melody again. He'd come back with another chorus, maybe, the next week until he had enough for an arrangement.

Most times he was like that that. He could like write 8 bars for another tune... or another tune. So that's the way he approached his Big Band. He was learning. It was like on-the-job training - learn as you go. He was learning how to write for big band, and he was so talented that it would sound great. And totally original; very original, you know?

PY: No, not especially. He was just interested in developing his writing. There was not much you could say. .. he had very good handwriting, he was very meticulous, the voice-leading stuff was, like, very few mistakes. Every once in a while you'd find a mistake, you know, but, what can you add to somebody who's presenting what he is trying to learn how to write? He's doing his thing. I mean, if I bring in a chart, no one can say “Pete, it should have a sax chorus there, or it should have brass here”.

Guys would say things like “This is too high”, but nobody would ever say, “This is too hard” (laughs), because he would be up to the challenge. Man, he would write some sax stuff that was like... the stuff he played! And that's very hard to write out. And he would write it out. Y'know, all those.. triplet, sixty-fourth note triplet figures.. (Sings).. All those kind of things.. his own, unique rhythms and stuff. Plus, nice bebop lines. Beautiful. Once we heard how it goes after reading it down a couple of times, then we would see how brilliant it was. So, there was not much you could input into the guys writing, you know?

SV: Do you know if he studied composition formally with anybody?

PY: I don't know. I doubt it. I really do. I think he was just, learning by rote. Bringing his stuff, listening to it, and if he liked it, he kept going with it. If he didn't like it, he would change it.

SV: When you guys got together and talked about music, or talked about, say, recordings that you liked, was there anything that you used to talk about, any specific recordings you were listening to? Do you remember?

PY: Well, obviously, you know, anything, Charlie Parker, anything under the stars. Sonny Rollins. He was into Monk. Anything Monk, he was crazy about. He liked some rhythm and blues people, the way they'd swing.

SV: Anything specific?

PY: Some of those sixties rock band guys, maybe, uh.. Slide (sic) & the Family Stone and., , Richie Havens., some people like that. Folk singers with serious swing..he would be listening to. He also liked listening to ragas and Indian Music. He also liked listening a lot to Stravinsky, and classical., you know, anything that was great. What we all considered great. He listened to them too. And he also listened to a lot of 'third-world' African bands, rhythmical, especially. I think he liked the African rhythmical, because he put some stuff on his telephone answering machine that sounded like African Music. He'd come on the machine and ..”Yeah, this is Joe, leave a message” (laughs), and stuff like that. But he was into it definitely. And it was anything, anything.

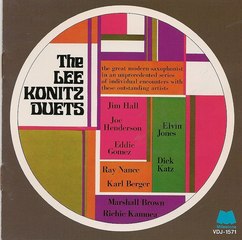

SV: Was it his album, or Lee's?

PY: No, it was Lee's album. He played some duets with Joe, just unaccompanied.

SV: I'll have to look it up.

PY: Yeah, you've gotta find that., it's one of Lee’s albums. Duets it's called. It's some different duets with different groups.. A couple with Joe.

When I was with Joe's sextet, we used to drive to gigs and I'd usually drive cause he didn't have a car. Then I'd talk to him a lot in the car about his philosophies. So I got to know the way he was thinking. His attitude about jazz was very unique. He had this attitude of...when you get to the bandstand, that's when you try stuff out. It didn't necessarily have to be a finished product.

He liked to experiment right on the bandstand., and of course he had so much skill already that he brought to it that, you know, he had the ability to experiment. That was one of his attitudes. He would try things on the bandstand. Especially in the sixties, when experimentation and people were playing “out'”, like really “out, out”... He was into that, he loved that. And he'd like, sometimes, sing a bass line, to the bass player, and then,..Stanley Clarke, who was playing bass at the time would just get the bass line and the tempo would start, and he'd start playing. And they would go wherever it goes.

SV: I think there's one tune on that album, the Milestone album, like one that you and Stanley Clarke, and George Duke..

PY: Yeah.

SV: And Joe, and Woody., is Woody Shaw on that? I don't know if Woody Shaw is on that track.. They say in the liner notes that the guy asked him a question and says 'What's this song?'. I can't remember the name of it off-hand but he says “Yeah, I just took the theme and I just went, you know, to see where it would go”.

SV: I read that he was influenced by literature. He read a lot.

PY: Yeah he did. He was very intellectual. He was reading Thomas Mann, uh...”Magic Mountain”, and he was also reading “The Bead Game”.

SV: Yeah, Hermann Hesse.

PY: He named it.. Hesse, yeah. And like I said he was reading a lot of Eastern literature..he was reading all that, uh.. Jack Kerouac, all that hippy stuff that was coming out in the sixties. He was reading a lot. And of course, then, later on he got into languages. He started to study. He already could speak like, three or four languages, fluently. And then he started studying Japanese because he was constantly going to Japan so he started teaching himself Japanese and I think he's doing very well with that. Very intellectual.

SV: And I guess, does that go back to his family?

PY: I think so. You know, I’m not sure. I've met his mother-she's kinda older, a little bit feeble when I met her, but, yeah, he has eleven brothers or twelve brothers.. Some of them are MIT scientists. I think they're all successful and very intellectual, that whole 'strain'. I met his brother who's very smart and very sharp, so I think it's the kind of thing that runs in the family, you could say.

SV: Did you practice with him in his apartment?

PY: I never practiced with him. But I used to hear him practice. He used to practice a lot, you know, but I didn't practice with him. But I know he used to work very hard, working out some of those rhythms, some of those substitute changes. He used to be at the piano all the time. You know, he was constantly working, constantly developing himself.

"Bird" - Charlie Parker

"Bird" - Charlie Parker PY: Oh Yeah, definitely. I mean, he'd do everything everybody does. In the beginning you could see that he did a lot of transcribing. Matter-of-fact, he told me and he told the workshop that I had him at LIU, which is where I teach - I brought him over there and he did a workshop for us - and he was talking about practicing, and he said in the beginning he used to transcribe Charlie Parker solos, write 'em out and he learned the language that way.

He also learned to hear what the piano was doing behind Bird and so forth and how the drum figures.. 'cause he was there in Lima, Ohio or something and it was very hard to hear, to get to hear any live jazz there, so he learned off records, but then he would go to Detroit and he'd play more there.

SV: Did he ever talk about his aspirations?

PY: Yeah, he wanted to be the best saxophone player that he could be, or that ever could be. He wanted to be the best, period, number one. He had a lot of pride,y’know. He's competitive but in a quiet way. And he'd just work hard to be the best, you know? And I think he achieved it. He was the best, if there IS a best. I don't know if you can describe it. It's a personal thing. Like, I like how so-and-so plays even if so-and-so has no real technique but has a sound and an approach that's funky.

So, let's say, for instance, Stanley Turrentine. A lot of people might have preferred Stanley Turrentine to Joe, but., like, I remember going to a gig where they were both playing, two bands playing, and Turrentine was breaking everybody up, he was getting over, unbelievable, and Joe's stuff was just going right by everybody, y'know, because it was so amazing and so incredible. It's hard to compare, who's better. But in my mind, there was nobody, no technician who could do the things Joe could do..the top and the bottom of the horn, all original stuff, that everybody was stealing. That's another thing. Everybody was stealing his stuff.

SV: Even at that time?

PY: Absolutely. As soon as he'd come out with a record and his approach to the record - his approach to the tune, especially the ones with Horace., everybody would immediately start playing like that. It was like 'Trane; the same effect 'Trane had on people. 'Trane came this way, and everybody started playing like that, and 'Trane went out, and the modal thing and everybody started going out. Sonny Rollins had that effect, and Bird had that and Joe Henderson had that. He was so charismatic, y'know, people just wanted to play like him. You hear that, you just want to play that way.

SV: Did you hang out with him in Detroit at all? That was when he went to Wayne State, so I guess that was before you met him, right?

PY: Yeah, I hadn't met him.. I heard him about him in Detroit. I heard a record he made, or a tape he made in a club and he sounded like Charlie Parker but on tenor. He just like, had ALL of Bird's shit down - unbelievable. Yeah, he was playing all the shit, he was playing Lover on this tape. As a matter of fact, Javon Jackson, the tenor player, has this tape.

I studied Bird, really, really deep. I was trying to play a lot like Bird and I almost couldn't play a tune unless I heard Charlie Parker play it first, and I was playing all the licks and everything. Joe, and I think Charles McPherson,.... I never heard anybody get close to it like that. I think I was in that area for a while, but then, I guess I knew that I had to get out of there, stop playing like Bird, or else (laughs) I'd be in trouble.

PY: Well, Yeah... it definitely changed. When he was younger his playing was exuberant, and youthful. His chops were up and he was experimenting, like I said, and his sound was still vibrant. As he got older, everything matured and got mellower. I think it's obvious.. When he won the Grammy that, "Lush Life" got, it was a kind of a 'mellow' Joe Henderson, you know, 'cause the Shade of Jade and those albums are hard-core. Joe Henderson's tunes, are really difficult - a lot of changes, and the chords have a lot of tensions in them: b5Maj7 chords, and moving in all kinds of patterns. You could hear the math, and the way he thought compositionally.

He was playing harder and longer solos. So many times when I heard him, he was just so incredible. He was just playing so much stuff, you know, that nobody could keep up with him. It was just so beautiful, the rhythm section - he would just leave them..somewhere, WAY behind him! He just soared out above everybody. 'Trane had that ability, you know. And 'Trane finally hooked it up with Elvin. That was a smart thing 'Trane did, 'cause they became a tandem, that could do all that, with McCoy. So that worked.

If Joe could have kept a band that was up to his level, that probably would have been the best thing, but, the business in the '60's was so difficult that you couldn't really keep a band, you couldn't keep working. The work was too difficult, so Joe had to keep getting different bands, and playing with different people. People quitting, and going this way, going that way, going into rock, going into the fusion thing. Even Joe tried some fusion...

SV: His own stuff?

PY: Yeah.. Well, he made made some funk albums, but, they were sort of fusion albums, I would say. But that was a slightly different time, you know. There was like, ten years difference (in age) between 'Trane & Sonny Rollins and Joe Henderson. So those guys were able to play more “in there”. Sonny Rollins played with Clifford Brown, and he was really able to develop at Blue Note with the same band. Joe got the chance with Herbie Hancock and Horace, but when he went on his own he couldn't keep a set band together. He tried but it didn't work out that well.

SV: Did that have anything to do with the record-company label support?

PY: Yeah, it has to do with all that. They wanted him to record a rock, a funk album, they wanted him to use certain people all the time, you know. And these labels start telling you what to play, who to play with and what to record. Stuff like that. He actually even won a Grammy. I think it was all the record label when he won the Grammys. The thing at that time was to have a theme for your album ; so this is tunes by Strayhorn, or by Ellington. And, so that's why the company put that together for him. They hired Christian McBride, and whoever, 'cause he wasn't playing with Christian McBride at the time.

JoHen & Friend

JoHen & Friend PY: See, that's another example of Joe trying to make some money and keep working. It was very hard to make money. A guy of that caliber and that talent, and trying to make money. When "Blood, Sweat and Tears" comes and offers to put him on salary. And, you know, play with the band and so forth, he just said, “Yeah! 'Cause, you know, I have expenses. I have things I like to do in life”.

He had a dog, he had a very expensive dog - an Afghan! He had an Afghan, he had a motorcycle, he had a lot of things that he enjoyed. He had them right here in Brooklyn. And, he wanted wanted to pursue some things, he wanted to have a good life. So, here comes some money down the road. So he took it.

SV: Did he like it?

PY: Blood, Sweat, and Tears never worked out because I think that he never was interested in the music that much.

SV: Did he get to do some writing for them, some arranging or anything like that?

PY: Umm. I don't know if he had any 'eyes' to do that. I don't think the rhythm section or those people were on his level. I think he still wanted to play jazz more than anything. He just knew that he could do some funk and just make some money , you know, his head wasn't into it... he never talked about it a lot though.

SV: He didn't talk about it, I see. What did he like talking about - mostly about philosophy, you said? Did he have any ideas or something that was unique to other things that he talked about philosophy?

SV: That's interesting.

PY: Yeah, it was a very weird thing and.., we used to talk about it. It had something to do with drugs, and the philosophy of taking drugs, and., how, while some people collect money, other people are strung out on, you know, like material wealth, and some people are strung out on heroin and some people are strung out on this or that, or cars, or anything.

So, it's very hard, he was saying, to judge what's good and what's not good. Well, collecting money in this society is supposed to be a good thing, it shows someone is powerful. But it's really just as evil to be greedy as being a junkie, which is not evil and greedy, it's just, something that you do. He had a rationale for some of his pursuits. He had this thing where he could justify, could rationalize all of the things he was doing. Some of them were negative, some of them were positive, you know, and he was able to keep going with whatever he felt that needed doing. That was bad., or...people would say it was evil or bad for you.

I used to try to be the Devil's Advocate - I didn't agree with what he was saying. I would say "But Joe, man, this is destructive, this is 'X', 'X', 'X', and 'X'. It's destructive. And it's bad for you. It's bad for your this, and it's bad for that, it's bad for your body, it's bad for your creative juices". And he would say " No - but look at so-and-so. He's an example of somebody who pursues this, and look how brilliant and amazing his life, and his contribution is." You know? And so then I would say "But, look, that might be good for him, but he's only one out of a trillion, man. So you know that fell off the tree, man. It's not right - you can't keep justifyin'." But he'd never get it. So that was just one interesting part of his philosophy.

In the sixties, the difference between good and evil was a very gray area. What's good for some is bad for others, and he would say... in politics, for instance, “democracy doesn't work in some places”. You can't impose Western., values on some of these Eastern people because it's different., they have a different style. So, you know, some religions are this way, some religions are that way - you can't impose your religion on people. It doesn’t work for certain people.

SV: Speaking of which, did Joe have any religious affiliation, or was he just spiritual?

PY: He was a spiritual person, in that he respected and knew a lot about religion and philosophy, but I don't think that I ever heard about him going to Church, although he respected the Church. He loved Gospel music and loved religious Indian music and the African music. He listened to all this music and you know like,.. folk music and stuff; a lot of it was religious oriented. But as far as I know he never went to Church or Synagogue, or anything like that, but I know that he respected the philosophies. 'Cause it was just a philosophy.

PY: Yeah. He has more than one., maybe three. He has a son, who lives in New Jersey. But he didn't raise the son. I think they've had a relationship in the past six or seven years., especially when he got sick. And I heard that his son went out to be with him in San Francisco. Last time I called him [Joe Henderson], he had a nurse - this was about, three months ago. The nurse was there and the nurse said that he was doing ok, but she didn't let me speak to him. I have a feeling that he's having trouble physically.

SV: He is having trouble physically?

PY: I think so. Because he's the kind of guy who., he would have to be at a high level of operation to want to come out, to play. Because he wants to be, like I said, the best, and he wants to be at such a high standard, that if he's not physically fit, he probably wouldn't want to come out and play.

SV: How did he influence you as a person; as a musician?

PY: Oh! In so many ways: to be open minded about music, about all different people, about peoples' contribution, about seeing how music that's not related to jazz can help you in your jazz music, in your music that you pursue. In philosophy, he influenced me a lot. There'd be that whole approach on the bandstand of trying things and not being afraid to take a chance on this and take a chance on that. And to think of jazz in that it's different from other music in the sense that you could go on the bandstand and you can experiment, and that it's ok.

I feel that it shouldn't have to be set up... three choruses, bass solo, and piano is, you know, like record dates, and stuff. That's anti-jazz in a way. Even on a record Joe would try to be “loose and see what happens” kind of thing. A lot of producers won't let that happen, but you know, there was a spirit in the '60's... When I get on the bandstand, even though I'll take the first choruses or something in the conventional sense, I'm still always thinking of what can we do here to open this up a little bit, or to make this a little more creative, you know. Let's play some stop time, let's play some without the rhythm section, or let's cancel out the piano and play with just the bass a little, something like that. Or, let's just trade with the drummer - I'll play with the drummer for a while. You know, stuff that's a little., a little bit experimental. It's not as wild and crazy as the Art Ensemble of Chicago, or one of those bands that's really creative...,but they can't play conventionally, you know.

So, I like a certain amount of convention, that's my, personal thing. But Joe helped to bring me out a little bit - being experimental on the bandstand, and also, his respect for music and his regard for the music. When he comes to the gig he means business. He gets up there, and he just plays the very, very best that he can possibly play and he never really plays “down” to the audience or tries to play “funky” when he doesn't feel “funky”, or whatever. He plays honest, real honest, you know, and he’s an intellectual. A brilliant guy, and that's what he plays. That's what he always did - this beautiful way of figuring out what to do to get his best stuff out, even, when he needed to play really soft, or really beautifully. He could play so many different ways, as you know. He could make that instrument sound like a flute, if he wanted to. Or he could play hard-core when he felt like it.

PY: Uh.. I don't know if he ever..., probably played it a little bit. I remember that he tried to play the alto one night, cause his tenor was broken. Didn't sound very good, you know, but he didn't have a setup. Y'know, alto is - this has nothing to do with Joe- but, alto is a very tough instrument. To really sound good, a good alto player, it's very hard for a tenor player to pick up an alto and sound like a good alto player. That's not easy. I don't know many people who could do it. Matter of fact, I can't even think of one except Sonny Stitt.

SV: (laughs) Sonny Stitt - I was going to say him.

PY: He's an alto player, and a tenor player. But I've heard guys, often pick up an alto, like Joshua Redman, or Joe Lovano.. they do not sound like alto players. They just sound like they're "playing the alto". To me, anyway. That's personal. As great as they are on their instrument.

SV: Do you think Joe ever really got his due? Do you think he ever got what he deserved, in terms of his playing, do you think his music was appreciated at the time, or., do you think he achieved the type of success he should have achieved?

PY: Oh, definitely not. DEFINITELY not. Even though he won two Grammys, I think, and was nominated two or three times. Even though he did that, he didn't get his due until he was in his middle fifties. That's late, that's too late. He should have been getting that acclaim when he was with Horace, or when he was coming up with Herbie and all those groups. People should have seen the genius of him. But he was too good for people to hear. And also the fusion stuff was taking over. Jazz wasn't getting the acclaim in general.

When Joe was at the height of his powers, jazz wasn't getting as much acclaim. NOW, it's if Joe Henderson came on the scene., he'd be..., look how he can play compared to Wynton Marsalis. Look how much he can play. I mean, Wynton is a great musician, a great spokesman, a great role model, a great human being, a great historian, and everything. But look at what Joe played, man, compared to what Wynton played. I mean, it's not even comparable.

So, if Wynton is a Pullitzer Prize winner, Joe should have been getting those kinds of awards, 'cause to me, he's almost as powerful as Charlie Parker., as powerful as 'Trane, you know, the way he turned jazz around. People started combining the modal with the bebop, and he just brought the stuff to another area that was powerful.. I'm tellin' you, every tenor player, and many alto players who were coming up in NY: Michael Brecker included, and Bob Berg and all these guys - you can think of so many. They just imitated Joe Henderson, period. Imitated!

SV: I read an interview where someone asked Joe what he thinks of people emulating him, in their playing. And he said "You know, I think it's great, but, you know, when they like, come up with a solo and they quote me directly and they don’t say where it's coming from., that's uh.. that's theft!" (laughs)

PY: Exactly! You know, like Gary Bartz, for instance, who's a pretty original player, and a good friend of mine. He used to come with a tape recorder to Joe's gigs, and Kenny Garrett also. They used to come to all of Joe's gigs. But when it came to the liner notes or something, they would never give Joe his due. They'd say "Who are your influences" and they would all say, you know, the same old cast of characters (Laughs). They wouldn't say Joe Henderson - I can't figure it out. And even on that, you know that Jazz, uh.. did you see that Jazz....?

PY: Yeah. Ken Burns! They didn't mention Joe Henderson - I can't believe it! I don't think he even got one mention!

SV: I'm trying to figure out why? Why do you think that is?

PY: He's too... too hip for people. It goes right past people.

SV: He's too forward thinking?

PY: Right! They can't deal with Inner Urge. Only musicians can, but they...it's too hard. It's too "out", what Joe was playing! And what he was hearing and those rhythms he plays. It'd just go right past people. They'd just go "Oh my God". They can't deal with it! Until he still won a Grammy, finally. But he had to tone it down. Don Sickler, and the people who produced those albums figured out how to put Joe into a space where people could appreciate him.

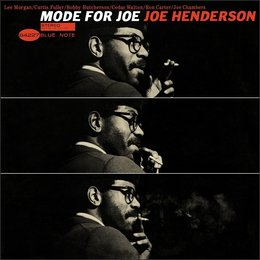

SV: Those Blue Note albums that he did from '63 to '67, they're so powerful - all the compositions, and of course, all the playing. Yet, I read that due to lack of support from the label, they didn't get that much play.

PY: Yeah, probably not. I don't know. I don't know the business that well. I haven't really followed Billboard - what albums are selling what, so I don't know. But, as far as I do know, every musician has 'em! (Laughs) And, all the guys were writing tunes that were similar to Mode for Joe, and all those. Oh man, that was such fertile, beautiful music - Chick Corea did whole arrangements on a bunch of Joe’s tunes.

PY: Yeah. There's two big bands on that album. There's one studio-type band, there’s one that's supposed to be Joe's big band.

SV: Are those the same charts that he put together before?

PY: Yeah. The ones that Joe wrote are the same ones that he wrote, like, twenty years ago. Look how fresh and good they are.

SV: Right. You guys didn't record though, back in the '60s?

PY: No. We didn't. This is the first record. That's why they put it together.

SV: That would have been something to compare the two bands. To see the differences in approach, or at least between the band that you played with in the sixties and the band that you played in on this recording.

PY: Oh, this later band – yeah. I don't know if there was that much difference.

SV: There are a lot of younger players in the recent band, right?

PY: Yeah, but the band that Joe put together which was supposed to be made up of the cats from the later band, was pretty close. Pretty close, but it didn't have the looseness, because nobody got to blow, except Joe. That was another thing that takes away from an album. You know, that's the producers again. Only Freddie Hubbard and maybe, a couple of piano solos to break it up a little bit. But, nobody else played any solos except., well, Freddie (Hubbard) played on the band that I played on, and Nicholas Payton was on the other one. Maybe another trumpet player.

But no other sax solos, I don't think there was any trombone solos. Just a couple of bass solos, by Christian (McBride). But, and then Chick Corea, of course, was on one of the bands, so he got to solo on a lot. He plays his ass off on that album. Just beautiful. But, you know, the whole spirit was that nobody was blowing on anything. So I think that takes away from the spirit. When you know you're going to solo, you're going to be heard, it makes you much more... alive.

SV: Did you go and hang out with him in San Francisco at all, when he was out there?

PY: Yeah, I met him in San Francisco, and we went out. I talked to him on the phone for about four hours from San Francisco., he was going to come to a gig that I was on. I went out there with the Machito Big Band. It was led by Mario Bauza at the time, and Joe was going to come to the gig. But, uh.. we talked for about four hours on the phone in the afternoon and he said that he'd see me at the gig and he never showed up; but I never went to his house.

PY: He played at ALL the jazz clubs.

SV: Do you know, approximately, when he left New York and moved out to San Francisco?

PY: Not really..., seventy something. I think Orrin Keepnews had something to do with it, 'cause Orrin Keepnews was working for a record company out on the West Coast. And Joe was recording for them. So he moved Joe out there. And Joe found a house. But I don't know dates.. seventies, definitely.

SV: Did he like it out there? What took him to... I mean, apart from Orrin Keepnews, was it the environment or was it..?

PY: I dunno. It's a laid back lifestyle, it's nice weather, probably easier to live there than New York City, you know. I mean, a LOT of cats went out there at that time. Freddie went out, Herbie Hancock went out, a lot of cats. Because at that time, if you were an international star, you didn't have to be in NY anymore. You could just do your business, you know. Fax machines were starting to get popular. An agent would book you anyway. It's a nice lifestyle, to have a house and a pool. You couldn't have that in NY.

SV: I guess Joe was doing some teaching out at... Stanford?

PY: He was teaching at one of those colleges, yeah.

SV: Didn't he do something at Stanford Jazz Workshop, as well?

PY: Yeah... he was telling me he had some students. He got some students from this alto player who used to play with Charlie Mingus, who was out there.... John Handy.

SV: Oh, John Handy.

PY: Yeah he got students from him out there. He was teaching, but his lessons, I hear, were funny as hell. You'd go there, and he was upstairs or downstairs. And you can wait downstairs for an hour or more. Then finally he comes down and he might give you a couple of lines to play and then he cuts out. A funny teacher.

SV: Yeah, I heard a story where, someone went to have his first lesson with Joe, and he picked him up in the car. And Joe needed to drive him somewhere. So, this kid drove Joe to this place, and Joe said, "Ok. Just wait here, I'll be back". And Joe didn't come back, for, like, three hours..

PY: Oh Shit!!

PY: Really!? He didn't even take his horn out?

SV: That's what I heard. I forget who I heard it from, this was a long time ago.

PY: I didn't know that Joe. You see, I didn't know that crazy Joe. I just knew Joe like a spiritual guy, we just used to hang out and talk; but I never knew the Joe, this teacher who was so evasive - "the 'Phantom" and what not.

SV: Why "the Phantom"? How did that name come about?

PY: I don't know. Because he's like.... very hard to pin down for some people. He doesn't like to hang out with a lot of people. I don't know why. He and I, our vibe was just really cool all the time. I mean, even when I was on the road with some band - I was on the West Coast with Bob Mintzer's big band one time and Joe was on the same bill. He was playing with his trio with Al Foster and the bass player.

So, after the set, I met Joe after and we hung out all night. He didn't want to hang, he just wanted to get away from the crowd. Everybody was getting to hang out with him, so he just ran away and said, "I'll meet you at the hotel - let's get together”, you know.. He liked to hang with me. Whenever he got a chance to he did. We'd hang for hours and hours and hours. And he felt comfortable. To do whatever he wanted to do, and it was cool. And we just talked and he'd tell me about this country he was in, and how the money was all crazy. Brazil, he thought the finances in Brazil were just — there was so much inflation, the money was so weird.

SV: When he was doing the stuff with Jobim?

PY: I don't know. They just brought him down to play. Maybe he was doing a concert, a big concert. They brought him down there, and he was just telling me how musical the country is, it's an amazing country for music. That they play even on the airplane the music that they play. They used to play during the flight while you were getting in your chairs, the beautiful bossa-nova rhythms. It was really something. He really loved it. You know, we used to talk shit like that. And, then we'd talk about inflation and the politics in this country and that country and his travels, and this is his shit and this scene that he was in and that scene that he was in, and whatever. You know, what he wants to do, he wants to get his band together, and all of the things that he has coming up.

SV: I guess you're very fortunate to get him to open up to you like that.

PY: Maybe so. I don't know. It's like, hopefully I was thinking that some his intelligence might rub off on me! (laughs)

Miles

Miles PY: Oh, he spoke Spanish, beautifully, French, beautifully, English.. I think he could speak some Portuguese, and he was studying Japanese. But the Spanish and French, and, maybe Italian - the Romance languages - he really could speak. He had a nice accent and everything.

I think he learned some of that in the army. He was in the army you know, he traveled around. His life in the army was interesting. He told me he originally played the bass. When he was drafted he took up the bass because that was the only instrument they needed. So he played the bass all around Europe. All over South America and all over Europe playing with an army band playing bass. And he, finally in some kind of way, switched over. He always played the sax, but not in the army. But he had a great time in the army. He loved his experiences. He didn't even have to wear Army clothes half the time. He'd wear civilian clothes and do jazz concerts.

SV: Did he ever talk about specific compositions, about how he composed..

PY: One composition he did talk about,... what was that? Yeah, it has a bass line, he took it from Stravinsky. Maybe it was Pursuit of Blackness... or.. No. (sings bass line) That's the bass line. It was a bass line that he got from Stravinsky, (goes to piano, plays bass line and melody). He got that from Stravinsky. He got some other stuff from classical music.

SV: Who did he like in Classical Music?

PY: Well, like I said, Bartok, Stravinsky, Alban Berg. You know, the twelve-tone..

SV: So he liked the Serialists?

PY: Some of it. But I think he was more into Debussy, more into Modem Classical. He appreciated all the best writers, but I know that Debussy was important to him. And probably Ravel. Everybody was into Impressionism, back in the sixties. Because it broke away from the Classical 'ii-V' stuff. And Impressionism was a free thing, or an open sound. And that's where jazz was going, you know. Playing on one chord for a long time and stuff like that. The seventies. Everybody was doing that.

SV: Did he mention playing with Miles?

PY: Yeah. He talked about Miles, but it was a very short thing. Miles had a rehearsal at his house, but he watched television the whole time. Miles hardly ever rehearsed anything, I think. Miles just said "You know the stuff, right?".

SV: (laughs)

PY: Yeah. And then Joe said "Yeah, Yeah". And he said "We'll get it together on the bandstand". And they went to the Village Vanguard. I was there, actually, one night. They played two tenors. Wayne played and then Joe played long solos trying to figure out the tunes and what not. But it was superfluous, - it wasn't necessary. It was too long. Every tune was a half hour. Then when Wayne would finish Joe would start. And then Miles' music didn't really lend itself to Joe's style that much.

Horace Silver & JoHen

Horace Silver & JoHen SV: (laughs) Oh, I see..

PY: 'Cause Horace, would keep a lot of the money, would make the big money in the band. Guys in the band didn't get paid well. I remember hearing Joe with Horace. I mean, Joe is not a dope. He was the star of the band., it wasn't even close. Horace is incredible, swinging and crowd-pleasing and knows the blues. Swings his butt off and plays great, quotes and things in his playing, but Joe, at that time, playing with Horace, he got the audience, man. The audience was screaming when Joe was playing. He'd do all his “out” stuff within the context of Horace's funky tunes. It was so hip.

I remember, I was in Washington - I was playing with Pearl Bailey and Louis Bellson big band - and we went to see Horace Silver when Joe was in the band. The band was in this one room, in this club, and there was a big lounge, and Joe was in the lounge with his tenor - I guess he was late for the set. He heard the trumpet player finish so he started his solo in the lounge. And he started walking into the other room up onto the bandstand.

It was so hip and slick for him to do that. And then he would, started playing. He took the whole place over. I think that he was so heads and shoulders above, you know, cats in the band with Horace. He knew that he should be making some good money. He told me he learned some business things from Horace. I know that Joe wanted to have his own band. That was his, you know, he'd play his own music. He wanted to make the leader money, whatever. He deserved it.

SV: I don't know exactly when he went back to San Francisco, but there was a certain time period there when people said, quote, unquote, he wasn't "in sight" as much. He wasn't recording as much, and doing as much, putting out as much music.

PY: Oh, where, in San Francisco, when he was out there?

SV: Yeah.

PY: I don't know what his scene was, 'cause I wasn't there. He had a big band out there, but there was one point there that he stopped writing, he stopped. He was still playing his brains out, but he stopped writing, he stopped big band writing. He just started to get, I don't know, I wouldn't say lazy but just uninspired. You know, just, discouraged with the scene. But he was still playing on a lot of records as sideman, he was still doing it. And eventually, he won the Grammys, so, you know, he became like a Superstar.

Joe Henderson - Nine of Cups

Joe Henderson - Nine of Cups Then he could buy a car, and get an office, just like all the ball players do, 'cause he was making that kind of money, he was always playing with a trio most of the time. He was making up there near a million 'cause he was paying half of it - five hundred thousand to the government. So get a corporation started. Keep it away and actually do some good with the money.

SV: At that point, I guess....

PY: Oh, then he got sick.

SV: Is there anything you want to add, just to cap it all off; just something off the top of your head, something you want to add — your own feelings?

PY: I just think that what you said about being an unsung hero. He did have some good years. I think that if he had kept his health, kept himself together health wise, he could have been doing more stuff. He should have been on par with Wynton and you know, those people. He should have been doing that and he should have had much more recognition from a jazz (media perspective)... Ken Bums or any of those... and, writers (who) passed him by, I don't know why. I can't think of why.

But he'll always be one of my heroes! (Laughs) That's all I can say!

SV: Thank you very much. I truly appreciate it.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed