As I recall, I was about to doze off in the back seat, when Hermann remarked suddenly, “Saxophone players tend to practice a lot of patterns, don’t they?”

I must have answered something like “Yeah, I guess so. Why?”

“Well my daughter, who’s 12, started playing alto and she practices a lot of patterns.”, he replied.

I mentioned to him that I had a few students at the time and that I’d be glad to give her some lessons.

That, however, never happened, as I left Germany a short time later.

She doesn't seem to have suffered in the least because of it.

Quite to the contrary.

As "the apple doesn't fall far from the tree", so the saying goes, saxophonist / composer Carolyn Breuer has gone on to become one of the most recognizable and respected Jazz Artists on the European scene.

I caught up with her recently via Alexander Graham Bell's 140 year old invention.

Allan Praskin

Allan Praskin CB: Actually, with 12. I got the saxophone for my 12th birthday. Before that, I played piano and was kind of bored with it. I wanted to do something with a wind instrument, so then Hermann gave me the saxophone.

BSJ: Why saxophone?

CB: Because he (Hermann) had a band at this time with Allan Praskin (the American alto player).

BSJ: Wow, Allan!

CB: He really impressed me with his alto sound and the way he played, which I thought sounded to me like heaven. Hermann took me a lot of the times to his gigs when he was playing with Allan......I wanted an alto saxophone (laughs)!

BSJ: Besides Praskin, who were your early influences on the instrument? Who were you listening to?.

CB: Actually, I started right away with Charlie Parker. Bird and Allan Praskin, these were my two heroes.

BSJ: Did you actually take lessons with Allan?

CB: No, but I went to so many gigs and he was always talking to me about the instrument and about tunes, so I picked up a lot just by being around him.

Actually, I went to a workshop that he was giving, when I was 14 or 15. I was kind of imitating him, maybe. I wanted to sound like he did, but couldn’t. He was playing these really hard reeds and I wasn’t sounding at all like him. When I was playing, he was always saying to me, “I like your sound! I wanna sound like you” (laughter)!

I think he was a big early influence and then Charlie Parker and I thought “Oh, this sounds easy” and then I discovered, “OMG, I took on the biggest genius of all, Bird, as a musical role model and I was kind of frustrated again (laughs).

Carolyn & Hermann Breuer.

Carolyn & Hermann Breuer. How much of an influence was Hermann on your musical development?

CB: One of the biggest! I mean, he was always there, he was always practicing and rehearsing. He was also a role model, you know. If you do it, then do it really…….not a little bit, not half. Do it 100%! Hermann is one of those musicians that when he plays, he’s giving you all he’s got.

BSJ: That’s definitely the Hermann I remember.

The Tree & The Apple

The Tree & The Apple So for me it’s a huge compliment that Hermann loves to play my tunes. He always wants to play them and check them out on the piano. For me this is a real compliment, because he wouldn’t just say it.

BSJ: Hermann raised you by himself?

CB: Uh huh.

BSJ: And your mother?

CB: Well, she died when I was ten and before that she was already somewhere else. I was most of the time with either Hermann or his mother, my grandmother.

CB: I had a classical saxophone teacher. He showed me technique and stuff, a lot of etudes and classical pieces written for solo alto saxophone. He was a very strict teacher who actually wanted me to become a classical saxophonist since I was always eager to learn, studied a lot and was kind of his “prize pupil”. He wanted to get me into the classical thing, but I just wasn’t into it.

BSJ: What was his name?

CB: Enrique Kropik. He was a friend of my father's and so he gave me lessons.

BSJ: Private lessons or through a music school?

CB: No, private lessons, but really every week from when I was 12 until I was 19, when I left for the Conservatory.

BSJ: So you studied with him for seven years.

CB: Yes, during that time I practiced a lot. When I was 16, I decided to leave school and just focus on music. There was a big fight with my father because he wanted me to finish school normally, but I didn’t want to.

I thought I would lose a lot of time (laughs) because I was so bored. I practiced saxophone and worked in a bakery to earn a little money and I prepared myself for Conservatory.

BSJ: What went into your decision to study in Holland?

CB: At that time (1988), in Germany, the only school offering a major in Jazz Saxophone Performance was Cologne.

In Holland, though, there were several Conservatories offering this program. There was Hilversum, The Hague. There was Rotterdam. Everyone I spoke to about it told me that the Dutch were a lot further along than they were in Germany since they had been offering this for twenty years already in Holland.

Plus, the teachers there were like the creème de la creme: trombone, Erik van Leer; Bart van Leer and Ack van Rooyen, trumpet; Ferdinand Povel, saxophone; there was really a high level of teachers.

BSJ: So you decided on Hilversum. Was your main teacher there Ferdinand Povel?

CB: Yes.

BSJ: What was his overall influence on your development as an improviser?

Ferdinand Povel

Ferdinand Povel I got quite far with this method up to the point that I went to the Conservatory. The reason I got accepted, I think, was because I played melodically and musically, but I had no idea about changes or of the possibilities of what you could do with them.

So in that regard, Ferdinand was a huge influence. He showed me everything, all the theoretical stuff, actually. Before that, as I mentioned, I had lessons with the classical teacher and with Hermann, who comped for me on piano and told me, “Close your eye's and try to find a nice melody.”

BSJ: Well, there's certainly nothing wrong with that, since that's really what it's all about.

The reason they call it “music theory” is because it's really analysis after the fact. Being able to “hear” what's in your head and manifest that spontaneously through your instrument is the ultimate purpose, anyway.

CB: Actually now, twenty years later, I’m trying to go back to that first way of playing and forget all this stuff, you know? Sometimes it’s like a curse that you know so much because you feel pressured to show it. I get bored with playing what I know. I want to be surprised, also, by myself.

At the same time I’m very thankful that Ferdinand explained everything to me in a way that made it all seem so logical. He was always very generous with his information, telling us students anything we wanted to know. I’m really thankful for that.

BSJ: He was also a helluva player. Still is, in fact.

So you were in Holland for how long?

George Coleman

George Coleman So I did my year, I liked it there and stayed, two years, three years. Then I thought, Ok, I’ll take the exam and get my degree. Then it became five years and wound up being 15 years!

BSJ: So you actually settled there. How long were you actually in school?

CB: Five and a half years. I got what I guess would be the equivalent of a Masters Degree, although I never thought about using it for anything.

After finishing school I went back to Munich for several months, but there wasn’t much going on, so back to Holland I went.

What’s maybe interesting also is that when I finished my degree, I twice got scholarships from Holland to go to New York. The first time I went, I studied with George Coleman and Vincent Herring and the second time I studied with Branford Marsalis; I mean, “studied” is a big word; I took a few lessons.

BSJ: What specifically did you work on with Big George?

CB: Well, he was, and still is I guess, into playing a tune in all 12 keys. That was the thing. We played Rhythm Changes and Cherokee through the keys. He showed me some things on dominant chords, whatever, but I don’t remember exactly.

CB: No, we played on the same festival, in Germany I believe. He was the main act and I was kind of a support act with a Dutch quartet in a club afterwards. The whole band came to check us out and afterwards he said that if I was interested he would give me some pointers and help me further, whatever.

At first, I thought it was probably just talk and was not going to happen. But we stayed in touch andwhen I got the scholarship, I went again to New York. The lessons were mostly, how would you say, a “kick”. He told me to stop playing only jazz standards and try to find my own tunes and melodies. He encouraged me to write my own music and go one step further than trying to sound like all the other guys. Yeah, that was actually the first step for me to start writing music; and a year later, in 2000, I released the first CD of my own tunes.

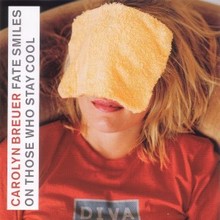

BSJ: Was that “Fate Smiles on Those Who Stay Cool”?

CB: Yes.

BSJ: I remember hearing your group at the present Unterfahrt in Munich, ca. 2001 and needless to say, I was quite impressed. It was also the first time that I actually heard you play, almost 20 years after first hearing about you from Hermann. I have the CD…..

CB: Is that the one with the napkin on my face?

BSJ: That’s right (laughs)! Can you tell us a little bit about that and the whole concept of why you went ahead and started you own record company and called it “Notnowmom”? Also, why the cover picture with what looks like a washcloth covering your face?

CB: Well, I did it because nobody wanted to release my CDs. I sent my recordings to all the usual record companies, but nobody wanted to give me a chance or invest their money in me. I was always kind of speechless. I just couldn’t understand why I was being rejected. I thought, “The music is good, I’m not exactly ugly. Why!?” But nobody was interested. So I said, “Ok, then I’ll do it by myself. Fuck them!” (laughter)

As for the CD cover, at that time there weren’t many role models for female jazz saxophonists, and the few that there were, were women who wore very revealing clothing on the cover and a lot of makeup. I just wanted to make a statement from the very beginning that “this is not about my face, this is about my music”, and the rest is not important. Just focus on the music, not on the face. I just got bored with all these….Diana Kralls, and blonde and beautiful………

BSJ: Well, since you no doubt belong to that last category yourself, I wouldn’t think it’d be something you’d want to hide under a washcloth forever, either. Aside from that one CD cover, though, I don’t think you have.

CB: Of course, now that I’m a bit older I think a little differently, but actually, that idea with the napkin was very smart. I didn’t know I was so smart (laughter)! It got a lot of attention, people saying, “what’s this?”.

BSJ: Very clever and effective. I’m sure you had people curious as to what was under that napkin. Why did you call it your record label “Notnowmom”?

CB: I just liked the three words “not now mom”. No reason.

CB: Because I had no budget for advertising, interviews, marketing, etc, I did this all alone from my kitchen table in Amsterdam, and I sold, like, 5,000 copies, from gigs and the internet.

BSJ: That’s terrific! If I remember correctly that was a live album, right?

CB: Yes. It was done in a studio in Augsburg with a small, live, audience, if you want to call it that. It was a typical jazz club atmosphere. Not too many people showed up. (laughs)

BSJ: So you’ve been back in Munich now for about 10 years. Besides the challenges of motherhood, what has been your focus musically in that time?

CB: Well, I came back with a recording contract with BMG in my pocket. They had released my previous CD “Serenade” which I had recorded with the Concertgebouw Orchestra in Amsterdam. I was full of energy and full of hope, in coming back with my first record contract and happy that I didn’t have to do everything by myself anymore. Things looked promising.

After three months, BMG was taken over by Sony and all the people who signed me lost their jobs, and my record was taken out of the program. I was basically left empty handed again. So, I decided the only way was to do it myself, once again and I’ve released several CDs since then.

I’ve written some new tunes and we’ve had several rehearsals already, which I’ve taped. I think it’s really so beautiful with the acoustic guitars and the horns. Hermann is playing trombone on a few tunes, and it’s really special, I think. Really nice!

CB: On some tunes, maybe. At the moment we have two acoustic guitars and they have everything: banjos, slide-guitars, dobros, classical and Weissenborn guitars. There will also be a string-quartet…..

When we get into the studio, we’ll decide how we want to produce it and what instruments we’ll use.

But the thing is, I….how’d you say,……I’m fed up with piano players! I can’t deal with them any more I need a break! (laughs)

BSJ: You wanna talk about that? Why are you fed up with piano players?

CB: Because there are so many possibilities and so many notes on the instrument (knowing laughter) and they play so many notes….. it’s driving me nuts, I’ll tell you!

BSJ: Have you ever done a pianoless trio, with just bass and drums? That can be a lot of fun!

CB: I would love to, but then you need a really kicking bass player and a kicking drummer (laughs).

BSJ: I think you could find a few of each in Germany, or in Europe (names several musicians).

BSJ: Well, that’s the other thing.

CB: That’s the other thing! You know if I ask (name) or (name), they’ll come play the gig, but that’s all. You know, this whole jazz mentality gets on my nerves. Everybody’s trying to play with everybody, and as many gigs as they can, but there are no real bands. Like in pop or rock music, you are a band, and if you are a band, you rehearse; you go for it! Everybody’s sacrificing a little bit for the main thing, you know. As a band leader, you are responsible for everything, and musicians who just come to the gig and are not willing to rehearse, I’m just……….!

BSJ: It’s difficult nowdays. It didn’t used to be that way, in my experience.

CB: Me too. I had my quartet for almost eleven years, and we rehearsed when we had no gigs. We were eager to rehearse. I remember one New Year’s Eve, none of us had a gig, so we got together and had a rehearsal until 6 o’clock in the morning on a little boat (on a canal) in Amsterdam.

BSJ: Wow! Now that sounds like a party!

CB: I miss this type of mentality. For my new project, I have musicians who are coming more from the rock scene and for them it’s so normal, that before you go to the studio, you rehearse for half a year. In jazz, it’s the other way around. First you record the CD and then you start rehearsing for the gigs, and then the CD usually sucks, until you start gigging and the band starts sounding like it should have sounded on the CD.

BSJ: That’s true, especially if you‘re doing your own, original music. It’s much more difficult, nowadays, to keep any kind of a band together, unless you’re funded somehow. It all boils down to economics, or rather, the lack thereof, usually.

However, if we do consider ourselves creative musicians, then coming together to create should be part of what we do, regardless of the economics involved, which will ultimately not only make the music the best it can be, but also special, giving you a tight sounding product you can potentially market. However, it seems that for most of us, it’s become all about “the gig”.

CB: Yeah, I think it’s very easy to be special, because the only thing you really have to do is rehearse!

Although, to be fair, maybe it was something that worked better when everyone was younger. That’s my explanation. When I was twenty-five and the people I played with were also twenty-five, we didn’t have a house, a spouse or children; we just wanted to play music.

BSJ: Well, I guess then, in that case, some of us never really grow up! (laughter)

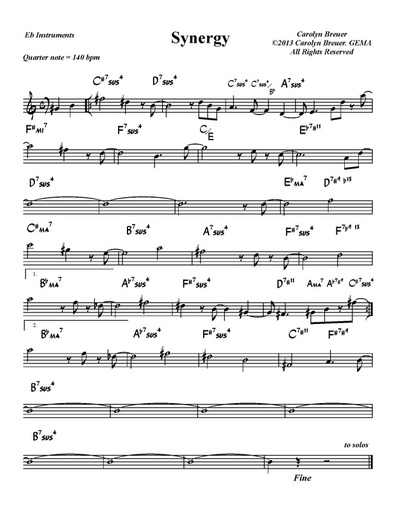

CB: Composing is, for me, a very intuitive process. As for the analyzing side of it, I do it later, when the tune is actually finished. With “Synergy”, I had the idea of the basic motif (sings first 2 bars).

I always take the basic motif and try to develop it with different chords. I’ll usually play the melody on the piano and I’ll look for the root (in the bass). Then I’ll close my eyes and sing where I feel the bass needs to go. This is the “secret” or the “magic”, I dunno. When I have the bass note, I’ll fill in the rest of the chord with the sound I’m hearing. In this case, the sus chords, they just sounded so damn good! (laughs)

It wasn’t that I decided “I’m going to write a tune with sus chords”, it was the melody, as a motif which I tried to develop further, at the same time as I was matching the bass line to what I was hearing.

I’m not someone who writes a lot of tunes, maybe two or three in a year. I need a magic moment, and there are not that many magic moments in a year. When I have this magic moment, then a tune comes out in, like, ten minutes or whatever. I’m not thinking about it, It’s just, whew, coming out of me. Then for the next three months, nothing is coming out! (laughs) So I wait for the inspiration, actually.

Sometimes I’m wondering about people who write tunes, for their own projects and they ask me to play it, and I think, “Well, I wouldn’t dare put this in front of a musician”, you know!? (laughs)

There’s one guy who’s writing like thirty tunes in a month, but I would not consider one of them as I tune. Just changes and a melody, but no magic in it. I think a tune has to have a certain magic.

BSJ: For me, “Synergy” definitely has it. That’s why after I heard it, I asked you for a lead sheet.

CB: Yeah, it’s not sounding constructed.

CB: I think they are nice changes to play on.

BSJ: How, theoretically, do you negotiate the sus chords in your solo.

CB: I’m thinking, for example, on an E7sus4, as B min.

BSJ: B Dorian?

CB: Right, B Dorian. That also makes it easier, I think, to see it that way.

BSJ: When did you write it, actually.

CB: Uhhh, shortly before I went back to Munich…….2002 or something like that, while I was still in Holland.

BSJ: Was it part of your quartet’s repertoire?

CB: Yes, we played it, but I never had the feeling that it would be good enough to be recorded. I think it really needed a back beat and a bounce, and at that time I wasn’t really satisfied with the feeling with which they played it. That’s why I didn’t record it at that time.

BSJ: So the recording with the WDR Big Band on your current CD was the first (and only) recording of it.

CB: Exactly, but not on purpose.

BSJ: How do you mean?

CB: I was a guest soloist with the WDR Big Band and they record everything. I had sent them a lead sheet before and Michael Abene did the arrangement for the band. The recording itself was just a rehearsal for a concert. Afterwards, they sent me the tapes to practice with, and I thought, wow, this should be released.

BSJ: Well, I think people will enjoy checking out the tune, lead sheet and solo transcription. I certainly have.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed